Expert-supervised-AI Cycle from Hypothesis to Real-World Materials Discovery

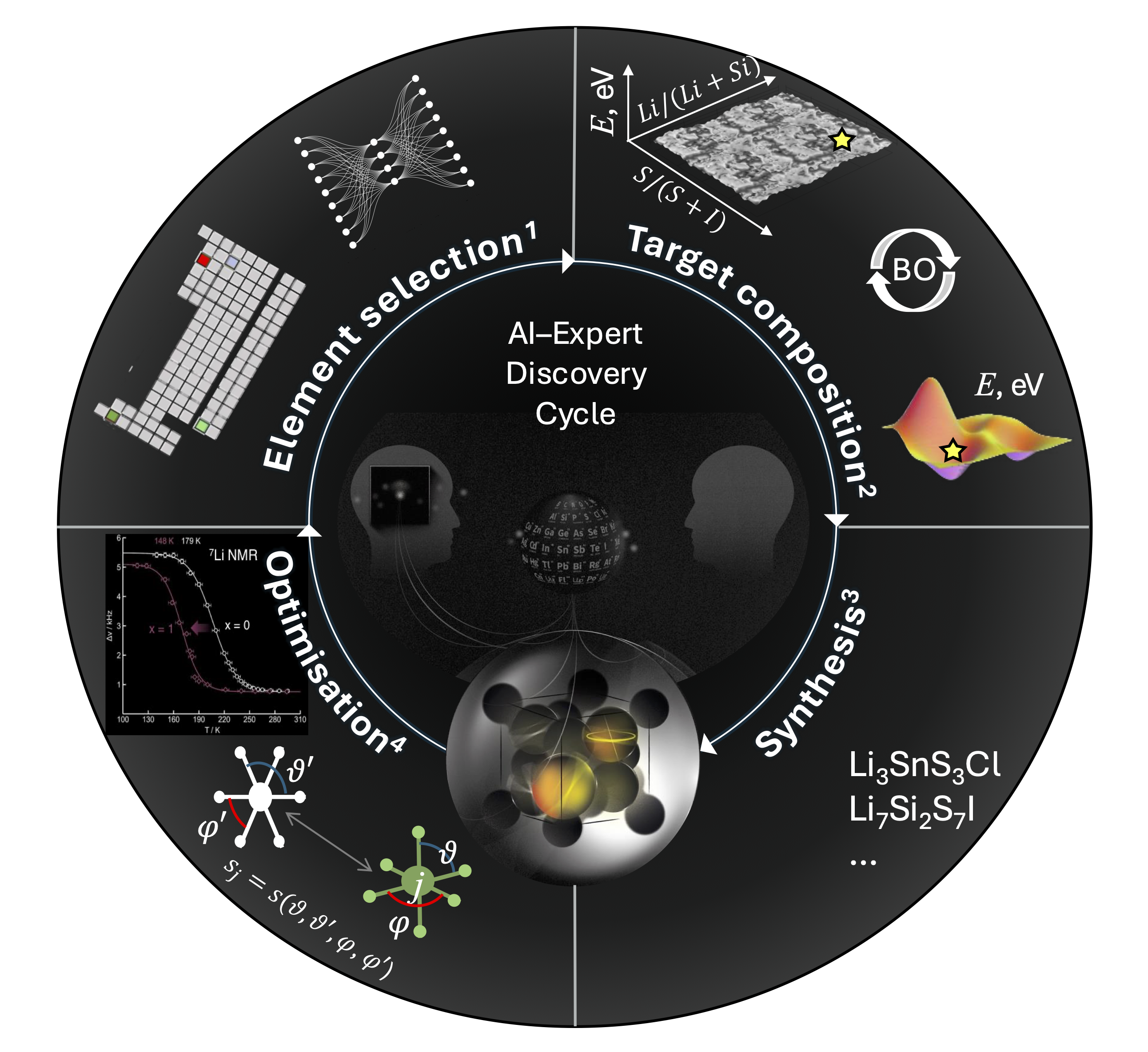

A vision of AI in materials science promises breakthroughs on an unprecedented scale: with AI now generating thousands of candidate material compositions, the transformative discoveries in superconductors, next-generation batteries, or water-splitting catalysts feel closer than ever. Yet there is a growing danger of science drawn into a maze of digital possibilities – suggestions that might dazzle on screen but steer humanity into a future of nominal advances and neglected experimental insights. In integrating AI with materials science, computational proposals need to be placed within a cycle of hypothesis, expert scrutiny, and experimental validation that balances predicted abstract patterns with realities of chemical behavior, real-world stability, and applicational demands. By treating AI’s output as provisional guidance rather than prescribed outcomes, we can develop a powerful AI-human interactive workflow that leverages digital tools1–4 to navigate the complex landscape of materials discovery (Figure 1).

In the important subset of materials such as inorganic compounds, through decades of mineralogical studies and synthetic chemistry, materials science has accumulated over 200,000 structures supported by experimental evidence5. This data collection is the basis of most AI applications in the field, from exploring elemental substitutions to predicting material properties6. As extensive as it may seem, this data remains limiting to exhaustive modeling, potentially biasing AI algorithms to familiar patterns, reemphasizing the importance of careful expert and experimental cross-checks to ensure that discovery does not simply mirror past knowledge but instead pushes boundaries. For example, elemental substitution into known compositions and structures is an established strategy and a convenient starting point in AI modeling7. However, such design by analogy requires original discoveries of parent materials, evolution of which through substitution often leads to incrementally modified rather than novel material structures and properties8.

.

To navigate beyond this foundational dataset, as the first stage of our workflow, we developed tools for evaluating the synthetic accessibility and chemical novelty of uncharted combinations of chemical elements, ultimately aiming to answer the fundamental question that chemists ask: “how to choose?”1. Exploiting the variational autoencoder’s (VAE) pattern recognition in the abstract latent space of a multi-dimensional chemical landscape, these tools afford ranking hypothetical elemental combinations by similarity to the experimentally explored data and focus our attention on the promising areas of the vast space of future materials. A VAE-selected set of chemical elements can additionally be prioritized for function, with relations between the choice of elements and betokened material properties uncovered by the first steps in explainable AI (XAI)9. With human domain expertise, this choice can be directed towards Lithium, one structural frame-forming metal, and two anions, which together may form a crystal structure with diverse geometries of lithium sites and low energy barriers conducive to ionic mobility; the discovery of such a structure could unlock a novel solid electrolyte and signal an all-solid-state battery breakthrough. However, even within this narrowed focus, each quartet of chemical elements expands a space of countless possible compositions, all requiring individual crystal structure prediction (CSP).

In exploration of this space, design by substitution discussed above and de novo CSP methods employ taxing quantum-mechanical computations and approximate materials by unit cells with a small integer number of atoms that periodically repeat in 3D to represent material crystals, hence omitting all compositions that cannot be expressed as integer numbers of atoms in a unit cell.

To fill these traditionally inaccessible-to-computation voids, we have hypothesized a continuous energy-composition relationship and applied AI to accelerate the exploration of the compositional space by directing CSP to targets with the most informational gain2. These energy-to-composition maps reveal close-to-stability compositions at a fraction of the cost and can focus experimental efforts on the most promising areas of the compositional landscape. Here, the cycle must return under expert supervision where among the identified combinations of elements and likely compositions, the choices are to test human hypotheses concerning new strategies for material design. For example, in crystal structures for superionic conductors, anions forming the intermetallic nets are hypothesized to facilitate high lithium conductivity, formulating a preferred structural criterion: a difference in ionic radii for the system’s anions. Thus, when selecting between highly VAE-ranked systems, Li-Si-S-Cl, Li-Si-S-Br, and Li-Si-S-I that unveil similarly low energy regions in compositional spaces, expert consideration of novel structural ideas highlights S-I combination for experimental trials, culminating in the synthesis of new superionic lithium conductor Li7Si2S7I (LSSI)3.

Novel structures can establish families of materials, where original discoveries become prototypes for optimization of desirable properties and structure through design by similarity and elemental substitution as discussed above. As such, LSSI lends itself to prototype optimization, where the selection of chemical elements for substitution or doping can be guided by the likelihood of retaining the original structure, as quantified by statistical/AI evaluation of local geometry prevalence in inorganic materials10. This optimization stage leads to the discovery of Li7Si2-xGexS7I materials, with x = 1 increasing lithium conductivity of LSSI in the low-temperature range, practically important from the application perspective4.

Materials discovery cycles increasingly benefit from synergizing human expertise with AI tools, which in tandem enhance our capabilities to address intricate challenges and the vastness of materials science. Emerging tools like generative models, large language models, and high-throughput simulations offer tempting avenues for science acceleration appealing to societal and industrial demands. However, the commitment of significant resources to large-scale application of these tools alone does not guarantee success, and presently, such strategies risk prioritizing numerical patterns over meaningful scientific advances. This emphasizes the critical role of expert supervision and the need for developing explainable AI to interpret predictions and uncover fundamental principles. With maturing XAI for hypothesis exchange and establishing trusted multi-agent cycles, materials discovery could evolve into a collaborative process reshaping scientific understanding and real-world applications.

References

- Vasylenko A., Gamon J., Duff B.B., et al. Nat. Commun. 2021; 12(1):5561.

- Vasylenko A., Asher B.M., Collins C.M., et al. J. Chem. Phys. 2024; 160(5):054110.

- Han G., Vasylenko A., Daniels L.M., et al. Science 2024; 383(6684):739–45.

- Han G., Daniels L.M., Vasylenko A., et al. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024; 67(37):e202409372.

- Zagorac D., Müller H., Ruehl S., et al. J. Appl. Cryst. 2019; 52(5):918–25.

- Agrawal A., Choudhary A. APL Mater. 2016; 4(5):053208.

- Merchant A., Batzner S., Schoenholz S.S, et al. Nature 2023; 624(7990):80–85.

- Cheetham A.K., Seshadri R. Chem. Mater. 2024; 36(8):3490–95.

- Vasylenko A., Antypov D., Gusev V.V., et al. NPJ Comput. Mater. 2023; 9(1):1–10.

- Vasylenko A., Antypov D., Schewe S., et al. Digit. Discov. 2024; DOI: 10.1039/D4DD00346B.